The Gallipoli Campaign of 1915-16, also known as the Battle of Gallipoli or the Dardanelles Campaign, was an unsuccessful attempt by the Allied Powers to control the sea route from Europe to Russia during World War I. The campaign began with a failed naval attack by British and French ships on the Dardanelles Straits in February-March 1915 and continued with a major land invasion of the Gallipoli Peninsula on April 25, involving British and French troops as well as divisions of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC).

Contents

Gallipoli Campaign Essay – Anzac Day Facts 2016 (Essay & Speech PDF)

Lack of sufficient intelligence and knowledge of the terrain, along with a fierce Turkish resistance, hampered the success of the invasion. By mid-October, Allied forces had suffered heavy casualties and had made little headway from their initial landing sites. Evacuation began in December 1915, and was completed early the following January.

The Gallipoli Campaign, also known as the Dardanelles Campaign, the Battle of Gallipoli or the Battle of Çanakkale (Turkish: Çanakkale Savaşı), was a campaign of World War I that took place on the Gallipoli peninsula (Gelibolu in modern Turkey) in the Ottoman Empire between 25 April 1915 and 9 January 1916. The peninsula forms the northern bank of the Dardanelles, a strait that provided a sea route to the Russian Empire, one of the Allied powers during the war. Intending to secure it, Russia’s allies Britain and France launched a naval attack followed by an amphibious landing on the peninsula, with the aim of capturing the Ottoman capital of Constantinople (modern Istanbul).[6] The naval attack was repelled and after eight months’ fighting, with many casualties on both sides, the land campaign was abandoned and the invasion force was withdrawn to Egypt.With Allied casualties in the Gallipoli Campaign mounting, Hamilton (with Churchill’s support) petitioned Kitchener for 95,000 reinforcements; the war secretary offered barely a quarter of that number. In mid-October, Hamilton argued that a proposed evacuation of the peninsula would cost up to 50 percent casualties; British authorities subsequently recalled him and installed Sir Charles Monro in his place. By early November, Kitchener had visited the region himself and agreed with Monro’s recommendation that the remaining 105,000 Allied troops should be evacuated.

The British government authorized the evacuation to begin from Sulva Bay on December 7; the last troops left Helles on January 9, 1916. In all, some 480,000 Allied forces took part in the Gallipoli Campaign, at a cost of more than 250,000 casualties, including some 46,000 dead. On the Turkish side, the campaign also cost an estimated 250,000 casualties, with 65,000 killed.

List of Events of the Gallipoli Campaign

August–December 1914

January–February 1915

March 1915

April 1915

May 1915

June–July 1915

August 1915

September–October 1915

November–December 1915

January 1916

History of Gallipoli Campaign

By early 1915 with deadlock on the Western Front and the Russian army struggling in the east, First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill sought to strike at the Central Powers on a new front in south-eastern Europe, knock Turkey out of the war and open up a much needed relief route to Russia through the Dardanelles.

The campaign began with an attempt to force the Dardanelles by naval power alone but early bombardments on the coastal ports failed and on 18 March 1915, three Allied battleships were lost to Turkish mines. In light of this failure, General Sir Ian Hamilton was appointed to command a 70,000 strong Mediterranean Expeditionary Force which consisted of the British 29th Division, a Newfoundland battalion, Indian troops, two divisions of the new and untried Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC), a Royal Naval Division and a French colonial division.

Its mission was to seize the Gallipoli peninsula and clear the way for the Royal Navy to capture the Turkish capital of Constantinople (now Istanbul). The 29th Division under General Sir Aylmer Hunter-Weston was to land at Cape Helles and push inland to capture Achi Baba while Lieutenant General Sir William Birdwood commanding the Anzacs would land further north at Gaba Tepe and strike the Sari Bair heights.

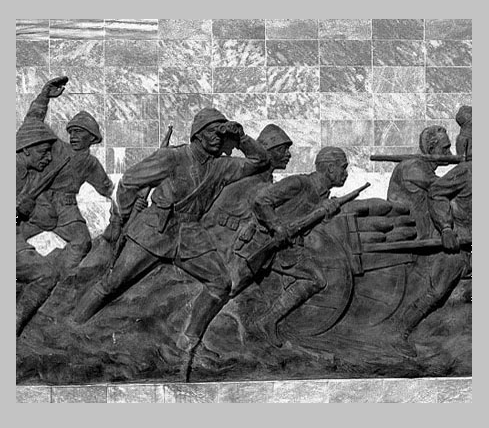

The attack was launched on 25 April 1915 but a combination of unexpectedly hostile terrain and ferocious Turkish defence soon stopped any potential advance and the campaign degenerated into the familiar deadlock of trench warfare. The Turks clung grimly to the high ground while the Allies below found it difficult to dig trenches impervious to their constant shellfire. As the deadlock continued, disease caused by extreme heat and unsanitary conditions would prove almost as deadly as the Turkish fire.

In August, Hamilton, with his force doubled to eleven divisions, tried to break the deadlock with an assault on Suvla Bay, and diversionary attacks at Helles and at Anzac. At Lone Pine the Anzacs were successful but unable to hold their position and at Sari Bair (The Nek) the Australians were cut down as they advanced. Later in August, New Zealanders, Australians, British and Indian forces attempted to take Chunuk Bair but were eventually forced back. The final significant actions took place on 21 August at Hill 60 and Scimitar Hill.

In October, with the campaign stalled, Hamilton was relieved of command. He was replaced by Sir Charles Monro who immediately recommended the Allies should evacuate. This proved to be the most successful part of the entire operation. Anzac Cove and Suvla Bay were evacuated in December 1915 and the Helles area was emptied of troops by 9 January 1916.

10 facts that you may not know about Anzac Day:

What some people don’t know is that all the men who fought during the eight-month battle at Gallipoli, including the 8,000 who died, were all volunteers. In other countries, soldiers were drafted (there was a mandatory sign-up) to fight in the war.

ANZAC Day is also observed in the Cook Islands, Samoa and Tonga.

There is a city called Gallipoli within the Gallipoli Peninsula but visitors to the area often stay in other towns close by like the ancient City of Troy.

The last-known Australian surivor of the Battle of Gallipoli, Alec Campbell, died in May 2002.

Originally, the term ‘ANZAC’ was used to mean any soldier who was a member of the army corps that fought at Gallipoli. While typically thought of as just Australian and New Zealand nationals, the ANZACs included officers from India, Ceylon, the Pacific Islands, England and Ireland. However, the term has subsequently been broadened to mean any Australian or New Zealander who fought or served in the First World War.

A soldier named Alec Campbell was the last surviving ANZAC. He died on 16 May, 2002.

The most significant time to remember the ANZACs is at dawn, as this is when the original Gallipoli landing occurred. The dawn service was first started by returned soldiers in the 1920s and originally, dawn services were only attended by veterans. Today, anyone can attend a service.

One of the key reasons for the failure of the Gallipoli offensive was the fact that the boats carrying the Australian and New Zealand soldiers landed at the wrong spot. Instead of finding a flat beach, they faced steep cliffs, and constant barrages of fire and shelling from the Turkish soldiers.

While the battle itself was a crushing defeat, the Australian and New Zealand soldiers were relentless and displayed incredible courage and endurance, even despite the most horrible of circumstances. This is how the ANZAC legend was born.

The Gallipoli battle itself ended in a stalemate, when the ANZACs retreated after eight months of battle.

The ANZAC spirit is wonderfully represented by a brave man – Private John Simpson Kirkpatrick. He was a stretcher bearer in the Australian Army Medical Corps, and spent his nights and days rescuing injured men from the battle lines in Monash Valley. He transported them back to the safety of ANZAC cove on his donkey. He is thought to have rescued over 300 wounded soldiers.

Another man who epitomised the ANZAC spirit was Charles Billyard-Leake. In 1914, he was living in a large manor in the UK – which he turned into a hospital for ANZAC soldiers. During the war, and for a while afterwards, over 50,000 Australians stayed at this Harefield Hospital.

The Last Post was typically played during war to tell soldiers the day’s fighting had finished. At memorial services, it symbolises that the duty of the dead has finished, and they can rest in peace.

ANZAC biscuits were believed to have made an appearance during the Gallipoli offensive. Made of oats, sugar, flour, coconut, butter and golden syrup, they were hard and long-lasting, and were ideal for troops in the trenches. They were apparently eaten instead of bread.

Professor Frame said the Anzac dawn service is unique to Australia, and adds another layer to what it means to be Australian.

Dr Knapman said the tradition belongs to all Australians.

“Every town is going to claim some connection to the Anzac Day myth; let them do it, it’s open to claim as much as they want.”

He said dawn services popped up around the country and there may be some which have gone unreported.

Dr Knapman said towns across the country holding ceremonies demonstrated the dawn service was a popular tradition which was not forced on communities from the top down, but spread from the bottom up.

Originally posted 2015-06-03 14:50:00.