Contents

Rabindranath Tagore Stories

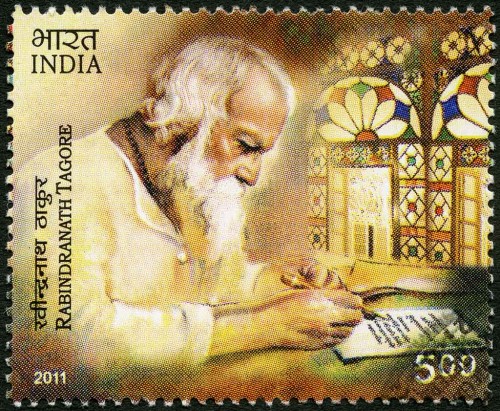

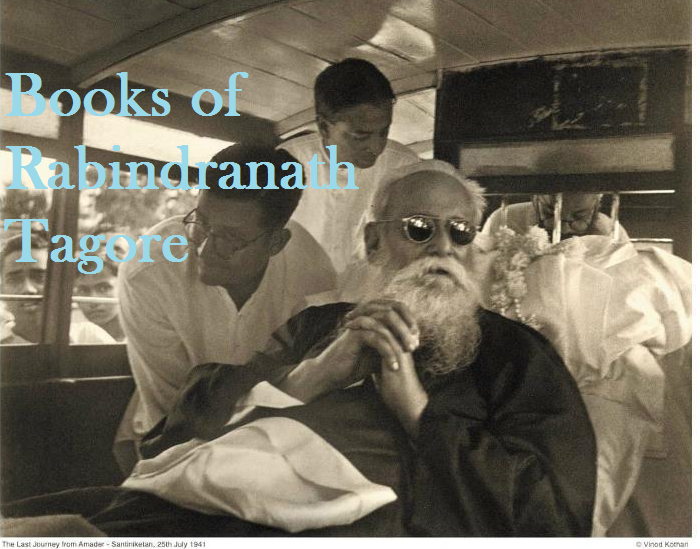

Tagore began his career in short stories in 1877—when he was only sixteen—with “Bhikharini” (“The Beggar Woman”).[1] With this, Tagore effectively invented the Bengali-language short story genre.[2] The four years from 1891 to 1895 are known as Tagore’s “Sadhana” period (named for one of Tagore’s magazines). This period was among Tagore’s most fecund, yielding more than half the stories contained in the three-volume Galpaguchchha, which itself is a collection of eighty-four stories.[1] Such stories usually showcase Tagore’s reflections upon his surroundings, on modern and fashionable ideas, and on interesting mind puzzles (which Tagore was fond of testing his intellect with). Tagore typically associated his earliest stories (such as those of the “Sadhana” period) with an exuberance of vitality and spontaneity; these characteristics were intimately connected with Tagore’s life in the common villages of, among others, Patisar, Shajadpur, and Shilaida while managing the Tagore family’s vast landholdings.[1] There, he beheld the lives of India’s poor and common people; Tagore thereby took to examining their lives with a penetrative depth and feeling that was singular in Indian literature up to that point.[3] In particular, such stories as “Kabuliwallah” (“The Fruitseller from Kabul”, published in 1892), “Kshudita Pashan” (“The Hungry Stones”) (August 1895), and “Atithi” (“The Runaway”, 1895) typified this analytic focus on the downtrodden.[4] In “The Fruitseller from Kabul”, Tagore speaks in first person as town-dweller and novelist who chances upon the Afghani seller. He attempts to distill the sense of longing felt by those long trapped in the mundane and hardscrabble confines of Indian urban life, giving play to dreams of a different existence in the distant and wild mountains: “There were autumn mornings, the time of year when kings of old went forth to conquest; and I, never stirring from my little corner in Calcutta, would let my mind wander over the whole world. At the very name of another country, my heart would go out to it … I would fall to weaving a network of dreams: the mountains, the glens, the forest …. “.

Many of the other “Galpaguchchha” stories were written in Tagore’s Sabuj Patra period (1914–1917, again, named after one of the magazines that Tagore edited and heavily contributed to).[1] Tagore’s Golpoguchchho (“Bunch of Stories”) remains among the most popular fictional works in Bengali literature. Its continuing influence on Bengali art and culture cannot be overstated; to this day, Golpoguchchho remains a point of cultural reference. Golpoguchchho has furnished subject matter for numerous successful films and theatrical plays, and its characters are among the most well known to Bengalis. The acclaimed film director Satyajit Ray based his film Charulata (“The Lonely Wife”) on Nastanirh (“The Broken Nest”). This famous story has an autobiographical element to it, modelled to some extent on the relationship between Tagore and his sister-in-law, Kadambari Devi. Ray has also made memorable films of other stories from Golpoguchchho, including Samapti, Postmaster and Monihara, bundling them together as Teen Kanya (“Three Daughters”). Atithi is another poignantly lyrical Tagore story which was made into a film of the same name by another noted Indian film director Tapan Sinha. Tarapada, a young Brahmin boy, catches a boat ride with a village zamindar. It turns out that he has run away from his home and has been wandering around ever since. The zamindar adopts him, and finally arranges a marriage to his own daughter. The night before the wedding Tarapada runs away again. Strir Patra (The letter from the wife) has to be one of the earliest depictions in Bengali literature of such bold emancipation of women. Mrinal is the wife of a typical Bengali middle class man. The letter, written while she is traveling (which constitutes the whole story), describes her petty life and struggles. She finally declares that she will not return to his patriarchical home, stating Amio bachbo. Ei bachlum (“And I shall live. Here, I live”).

In Haimanti, Tagore takes on the institution of Hindu marriage. He describes, via Strir Patra, the dismal lifelessness of Bengali women after they are married off, hypocrisies plaguing the Indian middle class, and how Haimanti, a sensitive young woman, must — due to her sensitiveness and free spirit — sacrifice her life. In the last passage, Tagore directly attacks the Hindu custom of glorifying Sita’s attempted self-immolation as a means of appeasing her husband Rama’s doubts (as depicted in the epic Ramayana). Tagore also examines Hindu-Muslim tensions in Musalmani Didi, which in many ways embodies the essence of Tagore’s humanism. On the other hand, Darpaharan exhibits Tagore’s self-consciousness, describing a young man harboring literary ambitions. Though he loves his wife, he wishes to stifle her literary career, deeming it unfeminine. Tagore himself, in his youth, seems to have harbored similar ideas about women. Darpaharan depicts the final humbling of the man via his acceptance of his wife’s talents. As with many other Tagore stories, Jibito o Mrito provides the Bengalis with one of their more widely used epigrams: Kadombini moriya proman korilo she more nai (“Kadombini died, thereby proved that she hadn’t”).

Rabindranath Tagore Short Stories {English Hindi & Bengali List}

Rabindranath Tagore Stories in Bengali

List of Short Stories

Sompotti Somorpon

Kabuliwallah(The Fruitseller from Kabul)

Ghare Baire (The Home and the World)

Jogajog (Relationships)

Nastanirh (The Broken Nest)

Shesher Kobita (The Last Poem or Farewell Song)

Gora

Char Oddhay

Bou Thakuranir Haat

Malancha

Chokher bali

Rajarshi 55

Korunna

Noukadubi

Tucch Bheet

The Postmaster

Samapti

Atithi

Dui Bon (Two sisters)

Charulata

Mrinal Ki chitthi

Rabindranath Tagore Stories in English

List of English Translations of Short Stories

With many of Tagore’s short stories, there has been more than one translation by more than one translator. For instance, The Supreme Night, One Night and A Single Night are all translations of the same story. Likewise, The Lost Jewels and Missing My Bejeweled are both translations of the same story.

The Auspicious Vision

The Babus of Nayanjore

The Castaway

Clouds and Sunshine

The Conclusion

The Devotee

The Divide

The Editor

Elder Sister

Exercise-book

False Hope

Finally

Fool’s Gold

Forbidden Entry

Fury Appeased

The Gift of Sight

Guest

Holiday

The Home-Coming

The Housewife

The Hungry Stones

A Feast for Rats

Haimanti: Of Autumn

Kabuliwala

The Kingdom of Cards

Little Master’s Return

The Living and the Dead

Living or Dead?

The Lost Jewels

Mashi

Master Zi

Epher Baluarte

In the Middle of the Night

Missing My Bejeweled

My Fair Neighbour

My Lord, the Baby

Once there was a King

One Night

The Parrot’s Training

The Postmaster

A Problem Solved

Profit and Loss

Punishment

Purification

The Raj Seal

Raja and Rani

The Renunciation

The Riddle Solved

A Single Night

Skeleton

Son-sacrifice

Subha the River Stairs

The Supreme Night

Taraprasanna’s Fame

Thakurda

Thoughtessness

The Trust Property

Unwanted

Uphaar

The Victory

Vision

“We Crown The King”

Wealth Surrendered

Wishes Granted

Rabindranath Tagore Stories in Hindi

Sacrifice – 1927 (Balidaan)

Milan – 1947 (Nauka Dubi)

Kabuliwala – 1961 (Kabuliwala)

Uphaar – 1971 (Samapti)

Lekin… – 1991 (Kshudhit Pashaan)

Char Adhyay – 1997 (Char Adhyay)

Kashmakash – 2011 ((Nauka Dubi)

Rabindranath Tagore Golpoguchchho (Bunch of Stories)

Tagore’s three-volume Galpaguchchha comprises eighty-four stories that reflect upon the author’s surroundings, on modern and fashionable ideas, and on mind puzzles. Tagore associated his earliest stories, such as those of the “Sadhana” period, with an exuberance of vitality and spontaneity; these traits were cultivated by zamindar Tagore’s life in Patisar, Shajadpur, Shelaidaha, and other villages. Seeing the common and the poor, he examined their lives with a depth and feeling singular in Indian literature up to that point. In “The Fruitseller from Kabul”, Tagore speaks in first person as a town dweller and novelist imputing exotic perquisites to an Afghan seller. He channels the lucubrative lust of those mired in the blasé, nidorous, and sudorific morass of subcontinental city life: for distant vistas. “There were autumn mornings, the time of year when kings of old went forth to conquest; and I, never stirring from my little corner in Calcutta, would let my mind wander over the whole world. At the very name of another country, my heart would go out to it […] I would fall to weaving a network of dreams: the mountains, the glens, the forest […].”

The Golpoguchchho (Bunch of Stories) was written in Tagore’s Sabuj Patra period, which lasted from 1914 to 1917 and was named for another of his magazines. These yarns are celebrated fare in Bengali fiction and are commonly used as plot fodder by Bengali film and theatre. The Ray film Charulata echoed the controversial Tagore novella Nastanirh (The Broken Nest). In Atithi, which was made into another film, the little Brahmin boy Tarapada shares a boat ride with a village zamindar. The boy relates his flight from home and his subsequent wanderings. Taking pity, the elder adopts him; he fixes the boy to marry his own daughter. The night before his wedding, Tarapada runs off—again. Strir Patra (The Wife’s Letter) is an early treatise in female emancipation. Mrinal is wife to a Bengali middle class man: prissy, preening, and patriarchal. Travelling alone she writes a letter, which comprehends the story. She details the pettiness of a life spent entreating his viraginous virility; she ultimately gives up married life, proclaiming, Amio bachbo. Ei bachlum: “And I shall live. Here, I live.”

Rabindranath Tagore Short Stories {English Hindi & Bengali List}

Haimanti assails Hindu arranged marriage and spotlights their often dismal domesticity, the hypocrisies plaguing the Indian middle classes, and how Haimanti, a young woman, due to her insufferable sensitivity and free spirit, foredid herself. In the last passage Tagore blasts the reification of Sita’s self-immolation attempt; she had meant to appease her consort Rama’s doubts of her chastity. Musalmani Didi eyes recrudescent Hindu-Muslim tensions and, in many ways, embodies the essence of Tagore’s humanism. The somewhat auto-referential Darpaharan describes a fey young man who harbours literary ambitions. Though he loves his wife, he wishes to stifle her literary career, deeming it unfeminine. In youth Tagore likely agreed with him. Darpaharan depicts the final humbling of the man as he ultimately acknowledges his wife’s talents. As do many other Tagore stories, Jibito o Mrito equips Bengalis with a ubiquitous epigram: Kadombini moriya proman korilo she more nai—”Kadombini died, thereby proving that she hadn’t.”

Originally posted 2016-01-25 09:52:22.